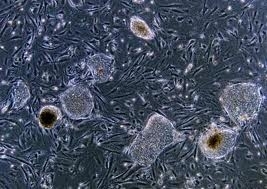

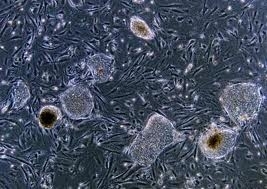

JAMES THOMSON, an embryologist at the University of Wisconsin, cultivated the first embryonic stem cell lines in 1998. By then the prohibition on using federal funds for scientific research in which human embryos are destroyed was already on the books: President Bill Clinton had signed it into law nearly three years earlier. So how did Thomson secure a government grant to finance his landmark achievement?

He didn’t. No government grant was necessary. His work was funded by the Geron Corporation, a California biotechnology company that develops treatments for cancer, spinal cord injuries, and degenerative diseases. Thomson was scrupulous about obeying the congressional ban, known as the Dickey-Wicker Amendment. The Washington Post reported that he did his research “in a room in which not a single piece of equipment, not even an electrical extension cord, had been bought with federal funds.”

Scientists and the government subsequently found a way around the Dickey-Wicker Amendment — they interpreted it as applying only to the destruction of human embryos required to extract stem cells, not to the research conducted afterward. So while the National Institutes of Health could not fund the actual cultivation of embryonic stem-cell lines, it could funnel taxpayer dollars to scientists experimenting with those lines. Last year, NIH provided $143 million for embryonic stem-cell research; so far this year, nearly 200 grants worth a total of $136 million have been approved.

But last week a federal judge in Washington pronounced that before/after distinction meaningless. Dickey-Wicker “unambiguously” prohibits the use of federal funds for (ITAL) all (UNITAL) research in which a human embryo is destroyed, Judge Royce Lamberth ruled, “not just the ‘piece of research’ in which the embryo is destroyed.” His injunction temporarily blocking the Obama administration from expanding NIH funding of embryonic stem-cell research has thrown the field into turmoil. Some 85 grant applications in the NIH pipeline have been stopped in their tracks.

Naturally, the ruling was heatedly condemned by supporters of embryonic stem-cell experimentation — The New York Times spoke for many in labeling it “a serious blow to medical research.” On the other hand, activists who oppose the harvesting of human embryos on moral grounds were pleased. Operation Rescue applauded Lamberth for a “ruling that will protect innocent human beings in the very earliest stages of development from death and exploitation through unethical experimentation.”

To my mind, there is no moral obstacle to using surplus fertility-clinic embryos that would otherwise be discarded for potentially life-saving medical research. Nor do I regard a microscopic cluster of cells as a human person entitled to full legal protection. Nevertheless, Lamberth’s ruling makes this a good moment to ask a threshold question: Why should the federal government be funding controversial medical research in the first place?

As Thomson’s original discovery proved, after all, pathbreaking accomplishments in stem-cell science are possible even when the government isn’t footing the bill. That was no anomaly. If the feds didn’t fund the search for embryonic stem-cell therapies, the private sector would.

As it is, a host of private funders are already pouring money into stem-cell research. Just last month, Geron, the company that underwrote Thomson’s work in 1998, announced plans to conduct the world’s first human clinical trial of a therapy derived from embryonic stem cells, a treatment for damaged spinal cords. And Geron is only one of many companies — Aastrom Biosciences, Stemcells, Inc., and Osiris Therapeutics are among the others — using private dollars to fund cutting-edge stem-cell research.

For-profit corporations and their shareholders aren’t the only source of private-sector stem-cell funding. The Washington Post reported in 2006 on the private philanthropy that was building new stem-cell labs on campuses nationwide. “Los Angeles philanthropist Eli Broad gave $25 million to the University of Southern California for a stem cell institute, sound-technology pioneer Ray Dolby gave $16 million to the University of California at San Francisco, and local donors are contributing to a $75 million expansion at the University of California at Davis. . . . Early this year, New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg quietly donated $100 million to Johns Hopkins University, largely for stem cell research.”

Add to them the Starr Foundation, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and all the other private charities that have made stem-cell research a priority — and those that would do so if the federal government declined to support research that so many taxpayers find problematic.

Douglas Melton, the co-director of Harvard’s Stem Cell Institute, told the Boston Globe last week that private support is “the only durable and consistent source” of funding for embryonic stem-cell research. He’s right. Medical research would not wither away if the government took a back seat to the private sector. In this as in so many other areas, perhaps the time has come to re-think Washington’s role.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

————————————————————————————————————————————

UPDATE: A new Rasmussen poll, released just after I filed this column, finds that 57% of American voters believe research on embryonic stem cells should be funded by the private sector. Only 33% favor federal funding.

There is no question that the American People should have Health Care. All the major nations have provided Health Care for their people. There is also no doubt that the United States’ Health Care Industry is one of the most advanced Health Care systems available.

There is no question that the American People should have Health Care. All the major nations have provided Health Care for their people. There is also no doubt that the United States’ Health Care Industry is one of the most advanced Health Care systems available.